Although the Coronavirus pandemic is currently the focus of news coverage, climate change continues to have an impact – subtle, but with an intensity that will change life on Earth in the long-term. Climate change threatens not only our quality of life, but ultimately the livelihood of humanity.

For our global economy, the question of how to reward capital for being used ecologically is becoming increasingly relevant.

We, therefore, implement the ESG concept in all corporate decisions. We follow the thesis that, in many cases, it is more resource-efficient to invest in older existing properties and to continue to operate them instead of always aiming for a new building or demolition/new construction.

What does this thesis look like in reality? The GARBE Research has calculated the life cycle assessments of existing developments and new buildings. The input parameters are largely based on building information from the current GARBE portfolio.

If a prospective tenant requires an area of around 30,000 m2 of hall within a large conurbation, the following options are available

Which approach is ecological and sustainable here? The decision criterion is the CO2 of these four options. On the one hand, the so-called embodied energy contained in the buildings is taken into account, i.e. the primary energy required to construct a building. On the other hand, the consumption energy is used, which includes the CO2 emissions generated by the electricity and heating requirements.

The ecological assessment of a hall is based on the CO2 behaviour of the property over a period of time – for example, the use of 20 years. The starting point is the beginning of use. All energy consumption figures are converted into tonnes (t) of CO2 equivalents p.a. and accrue annually. The embodied energy (also in tonnes CO2 equivalents) is only incurred once at the starting point of the analysis.

Furthermore:

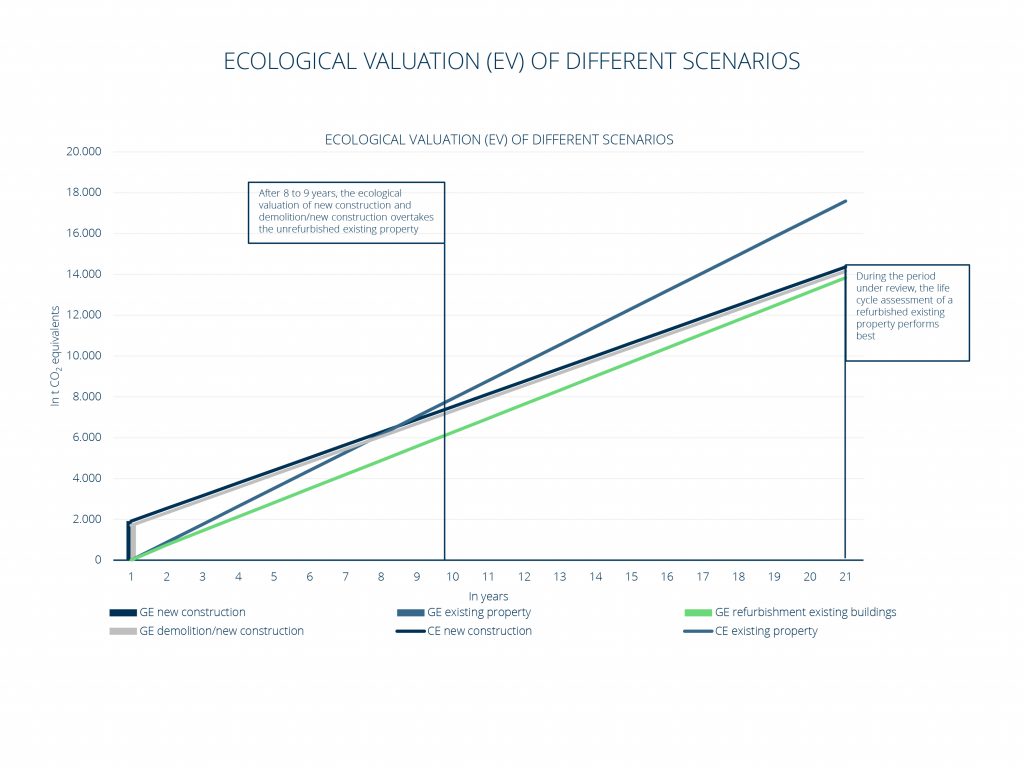

The following diagram shows that the CO2 equivalents are calculated over a useful life of 20 years after the start of use. The question is at what point the life cycle assessment of different buildings shifts in favour of another.

Refurbished and unrefurbished halls have a starting advantage due to the neutral embodied energy of the construction phase. Both new building variants, on the other hand, initially generate embodied energy, i.e. the curves already start with a “CO2 overhang”. It takes between eight and nine years for the higher energy efficiency of new greenfield construction to have a positive impact on the life cycle assessment. The life cycle assessment of demolition/new construction is even marginally better due to the recycling of materials during demolition. Otherwise, both development options behave identically. The life cycle assessment of a remediated existing property performs best over the 20-year period under consideration. Only after that would it be reasonable to assume that the CO2 footprint of the two new construction options would be ecologically amortized and perform better than a renovation property.

Many other aspects must be considered in the decision-making process, including:

For specific area-related questions, GARBE offers all real estate options. Together with our tenants , their space requirements are assessed for sustainability in both ecological and economic terms. The same applies to our investors, to whom we successively offer investment products geared to ESG guidelines.

ESG: Stands for a ecological and social sustainable corporate management and the responsible use of resources. For the society in which we live and work.

Learn more about ESGWe use cookies on our site. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and to show you personalised advertising. You can either accept all or only essential cookies. To find out more, read our privacy policy and cookie policy. If you are under 16 and wish to give consent to optional services, you must ask your legal guardians for permission. We use cookies and other technologies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience. Personal data may be processed (e.g. IP addresses), for example for personalized ads and content or ad and content measurement. You can find more information about the use of your data in our privacy policy. You can revoke or adjust your selection at any time under Settings.

If you are under 16 and wish to give consent to optional services, you must ask your legal guardians for permission. We use cookies and other technologies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience. Personal data may be processed (e.g. IP addresses), for example for personalized ads and content or ad and content measurement. You can find more information about the use of your data in our privacy policy. This is an overview of all cookies used on this website. You can either accept all categories at once or make a selection of cookies.